Fundamentals of System Design - Failure Models

Distributed systems consist of a set of loosely coupled services that end users perceive as a single coherent system. However, due to the loose coupling between components and communication over the network, failures are inevitable. Network congestion, a few instances going down, there can be a multitude of reasons that failure can be introduced in the system.

Timeout Management

Each retry attempt should have a reasonable timeout to prevent hanging indefinitely.

Without proper request timeouts, the service would consume excessive resources. For example, 100 requests per second, each using around 200 KB of memory, can accumulate ~1GB of memory to serve inflight requests. From the above example, if the timeout isn’t used appropriately, the service could run into out-of-memory issues pretty soon.

It’s also worth noting that the underlying work on abandoned requests should be canceled once the timeout is hit. Otherwise, the benefit of relinquishing resources will not take place.

A good metric for choosing the timeout value is the latency of the downstream service. Choose an acceptable rate of false timeout (0.01%). We also need to note the latency for both p99.9 and p50. If their latencies are similar, it’s better to pad the timeout value to avoid a small latency change causing high timeouts.

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

"time"

)

// Basic timeout middleware

func TimeoutMiddleware(timeout time.Duration) func(http.Handler) http.Handler {

return func(next http.Handler) http.Handler {

return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(r.Context(), timeout)

defer cancel()

// Create channel to signal completion

done := make(chan struct{})

// Run handler in goroutine

go func() {

next.ServeHTTP(w, r.WithContext(ctx))

close(done)

}()

// Wait for either completion or timeout

select {

case <-done:

return

case <-ctx.Done():

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusGatewayTimeout)

w.Write([]byte("Request timeout"))

}

})

}

}

// Handler that respects context timeout

func slowHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx := r.Context()

// Simulate slow operation

select {

case <-time.After(3 * time.Second):

w.Write([]byte("Operation completed"))

case <-ctx.Done():

// Context cancelled/timeout - stop processing

log.Println("Request timeout:", ctx.Err())

return

}

}

// Handler with database query example

func databaseHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx := r.Context()

// Pass context to database queries

// rows, err := db.QueryContext(ctx, "SELECT * FROM users")

// if err != nil {

// if ctx.Err() == context.DeadlineExceeded {

// log.Println("Database query timeout")

// return

// }

// // Handle other errors

// }

// Simulate work

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

log.Println("Context cancelled, stopping work")

return

default:

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Printf("Processing step %d\n", i+1)

}

}

w.Write([]byte("Database operation completed"))

}

func main() {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

// Apply timeout middleware

mux.Handle("/slow", TimeoutMiddleware(2*time.Second)(http.HandlerFunc(slowHandler)))

mux.Handle("/db", TimeoutMiddleware(5*time.Second)(http.HandlerFunc(databaseHandler)))

mux.HandleFunc("/fast", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Write([]byte("Fast response"))

})

log.Println("Server starting on :8080")

log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(":8080", mux))

}

For more examples, please check here.

Retries

Follow a strategy to avoid thundering herds, where the calls that failed at almost the same time are retried almost at the same time. Utilize exponential backoff and jitter. Exponential backoff, to wait longer on every retry, giving more time to recover to a potentially overloaded upstream, and jitter to introduce some randomness to avoid thundering herds.

Issues with retries:

- Drop in throughput: With a larger number of retries for the same request, the number of requests served by the server per unit of time gets reduced.

- SLA violations: Take SLA into account while setting retry count and timeout period

- Retry sparingly: Not all requests can or should be retried. The following status codes are perfect candidates for retry: 429, 500, 502, 503, and 504. However, status codes like 404 indicate client-side issues with request formation; hence, multiple retries wouldn’t change the outcome.

- Retriable operations: Be aware of the potential side effects of the operation

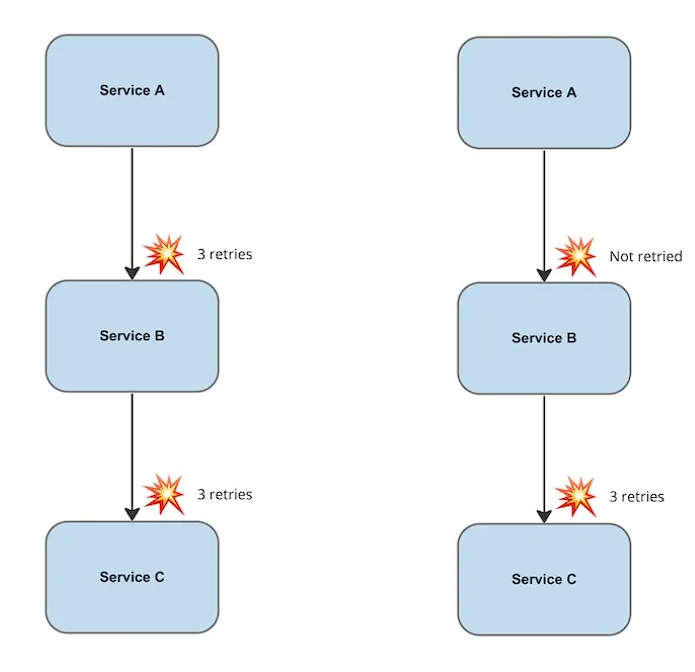

- Retry only on one level:

- Use Load shedding and backpressure: Upstream service should shed any additional requests that it can’t handle

Use Idempotent APIs to make retries safe

The majority of the HTTP requests are idempotent, except for POST and PATCH. Incorporate a unique caller-provided client request identifier into the API contracts. Requests from the same caller with the same client request identifier can be considered duplicates and handled accordingly.

Database Design Adjustments (Upsert Operation)

Prefer to use upsert operations (which update a record if it exists or insert it if it doesn’t) or apply unique constraints that prevent duplicates from being added in the first place.

Idempotency in Messaging Systems

Idempotency can be enforced by storing a log of processed message IDs and checking each incoming message against it.

Failover Caching

Most of these outages are temporary. Thanks to self-healing and advanced load balancing, we should be able to keep our service running during these glitches. This is where failover caching can help and provide the necessary data to our application.

Only use failover caching when it serves the outdated data better than nothing.

Circuit Breaker Pattern

The Circuit Breaker pattern prevents an application from performing an operation that’s likely to fail. A circuit breaker acts as a proxy for operations that might fail. The proxy should monitor the number of recent failures and use this information to decide whether to allow the operation to proceed or to return an exception immediately.

A circuit breaker consists of the following three states:

- Closed: The request is routed to the upstream service without any hindrance

- Open: The request failed immediately without invoking the upstream service

- Half-Open: A limited number of requests are allowed to invoke the upstream service

The retry logic should be sensitive to any exceptions that the circuit breaker returns and stop retry attempts if the circuit breaker indicates that a fault isn’t transient.

Service meshes often support circuit breaking as a sidecar or as a standalone capability without modifying application code.

package main

import (

"github.com/sony/gobreaker"

)

type ResilientPaymentClient struct {

service *PaymentService

circuitBreaker *gobreaker.CircuitBreaker

}

func NewResilientPaymentClient(service *PaymentService) *ResilientPaymentClient {

// Configure circuit breaker

settings := gobreaker.Settings{

Name: "PaymentService",

// Maximum requests allowed in half-open state before deciding to close

MaxRequests: 2,

// Time period after which failure counts reset in closed state

Interval: 10 * time.Second,

// Time to wait before attempting half-open state

Timeout: 5 * time.Second,

// Function to determine when circuit should trip open

ReadyToTrip: func(counts gobreaker.Counts) bool {

failureRatio := float64(counts.TotalFailures) / float64(counts.Requests)

return counts.Requests >= 3 && failureRatio >= 0.6

},

// Callback for state transitions (useful for monitoring)

OnStateChange: func(name string, from gobreaker.State, to gobreaker.State) {

log.Printf("[CIRCUIT BREAKER] %s: State changed from %s to %s",

name, from.String(), to.String())

},

}

return &ResilientPaymentClient{

service: service,

circuitBreaker: gobreaker.NewCircuitBreaker(settings),

}

}

func (r *ResilientPaymentClient) ProcessPayment(ctx context.Context, amount float64) (string, error) {

// Execute through circuit breaker

result, err := r.circuitBreaker.Execute(func() (interface{}, error) {

return r.service.ProcessPayment(ctx, amount)

})

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

return result.(string), nil

}

Load shedding and Backpressure

type LoadShedder struct {

maxConcurrent int64

currentLoad atomic.Int64

cpuThreshold float64

dropProbability atomic.Value // stores float64

}

func NewLoadShedder(maxConcurrent int, cpuThreshold float64) *LoadShedder {

ls := &LoadShedder{

maxConcurrent: int64(maxConcurrent),

cpuThreshold: cpuThreshold,

}

ls.dropProbability.Store(0.0)

// Background goroutine to monitor system load

go ls.monitorSystemLoad()

return ls

}

// Monitor CPU and adjust drop probability

func (ls *LoadShedder) monitorSystemLoad() {

ticker := time.NewTicker(1 * time.Second)

defer ticker.Stop()

for range ticker.C {

// Get current CPU usage (simplified - in production use actual metrics)

numGoroutines := runtime.NumGoroutine()

cpuUsage := float64(numGoroutines) / 1000.0 // Simulated CPU usage

// Calculate drop probability based on load

var dropProb float64

if cpuUsage > ls.cpuThreshold {

// Linear increase from threshold to 100%

dropProb = (cpuUsage - ls.cpuThreshold) / (1.0 - ls.cpuThreshold)

if dropProb > 0.9 {

dropProb = 0.9 // Never drop more than 90%

}

}

ls.dropProbability.Store(dropProb)

if dropProb > 0 {

log.Printf("[LOAD SHEDDER] System overloaded. Goroutines: %d, Drop probability: %.2f%%",

numGoroutines, dropProb*100)

}

}

}

// ShouldAcceptRequest decides whether to accept or reject a request

func (ls *LoadShedder) ShouldAcceptRequest() bool {

// Check 1: Hard limit on concurrent requests

current := ls.currentLoad.Load()

if current >= ls.maxConcurrent {

log.Println("[LOAD SHEDDER] ❌ Rejected: Max concurrent limit reached")

return false

}

// Check 2: Probabilistic rejection based on system load

dropProb := ls.dropProbability.Load().(float64)

if dropProb > 0 && rand.Float64() < dropProb {

log.Printf("[LOAD SHEDDER] ❌ Rejected: Probabilistic shedding (%.0f%% drop rate)",

dropProb*100)

return false

}

return true

}

// Acquire increments the load counter

func (ls *LoadShedder) Acquire() {

ls.currentLoad.Add(1)

}

// Release decrements the load counter

func (ls *LoadShedder) Release() {

ls.currentLoad.Add(-1)

}

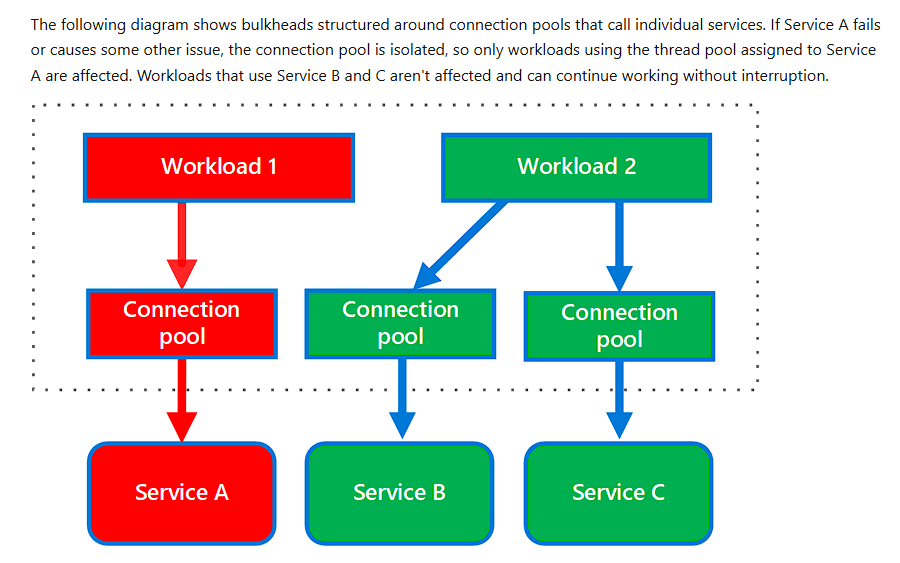

Bulkhead Pattern

Partition service instances into different groups, based on consumer load and availability requirements. This design helps to isolate failures, and allows you to sustain service functionality for some consumers, even during a failure.

// Bulkhead represents a resource pool with limited capacity

type Bulkhead struct {

name string

semaphore chan struct{} // Acts as a token bucket

maxWorkers int

timeout time.Duration

mu sync.Mutex

activeCount int

}

// NewBulkhead creates a new bulkhead with specified capacity

func NewBulkhead(name string, maxWorkers int, timeout time.Duration) *Bulkhead {

return &Bulkhead{

name: name,

semaphore: make(chan struct{}, maxWorkers),

maxWorkers: maxWorkers,

timeout: timeout,

}

}

// Execute runs a function within the bulkhead's resource limits

func (b *Bulkhead) Execute(ctx context.Context, fn func() error) error {

// Try to acquire a permit (worker slot)

select {

case b.semaphore <- struct{}{}: // Acquired

b.mu.Lock()

b.activeCount++

active := b.activeCount

b.mu.Unlock()

log.Printf("[%s] Acquired permit. Active workers: %d/%d",

b.name, active, b.maxWorkers)

defer func() {

<-b.semaphore // Release permit

b.mu.Lock()

b.activeCount--

b.mu.Unlock()

log.Printf("[%s] Released permit. Active workers: %d/%d",

b.name, b.activeCount, b.maxWorkers)

}()

// Execute the function

return fn()

case <-time.After(b.timeout):

return fmt.Errorf("bulkhead %s: timeout waiting for available worker", b.name)

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err()

}

}

References

- The two friends of a distributed systems engineer: timeouts and retries

- Mastering Exponential Backoff in Distributed Systems

- Timeouts, retries, and backoff with jitter

- Retries Strategies in Distributed Systems

- Making retries safe with idempotent APIs

- Designing a Microservices Architecture for Failure

- Mitigating Downtime: Strategies for Building Resilient Microservices

- Articulating graceful degradation strategies in architectural design

- Go Concurrency Patterns: Context

- Go Concurrency Patterns: Pipelines and cancellation

- Container-aware GOMAXPROCS

- Bulkhead pattern

- How tech giants like Netflix built resilient systems with chaos engineering

- Mastering Microservices Patterns: Circuit Breaker, Fallback, Bulkhead, Saga, and CQRS

- Circuit Breaker pattern